Moving aquaculture out to sea could rescue coastal ecosystems

Fish ponds have scarred coastal environments in Asia, but offshore fish farms might save wetlands and improve yields

chinadialogue

ocean

Along the shore of northern Java, the most densely populated island in Indonesia, they thought they had it made back in the 1980s, when the craze for turning mangrove swamps into prawn ponds took hold. Prawn prices were high. Village after village took the bait. “We wanted to raise some income and feed our families”, says Maskur, a teacher in Wedung, a large village on the River Wulan.

But now they are living with the consequences. The loss of their protective coastal strip of mangroves triggered an invasion by the sea that has engulfed many of their ponds in the past two decades, and eaten into the rice fields further inland.

“We’ve lost 500 metres to the sea in the last 10 years,” said Maskur, as our boat headed out into a bay unmarked on any maps. We passed the submerged remains of banks that had once surrounded village ponds. “I bought 10 hectares of ponds here in 2004, but three years later they were swept away,” said village official Nor Khamed.

Now the villagers are desperately trying to restore their mangroves, working with the Netherlands-based environment group Wetlands International to replant and erect brushwood barriers offshore that they hope will capture silt and hold back the eroding waters.

Across much of south-east Asia, the prawn bonanza is over. Many ponds, like those in parts of northern Java, have been plagued by coastal erosion. Others have been hit by diseases. And governments are clamping down on mangrove destruction to protect their coastal ecosystems.

But other forms of coastal aquaculture continue to surge round the world – from salmon cages in Norwegian fjords to backyard ponds stuffed with catfish across the Mekong delta, and oyster beds in Florida to carp pens off the coast of China.

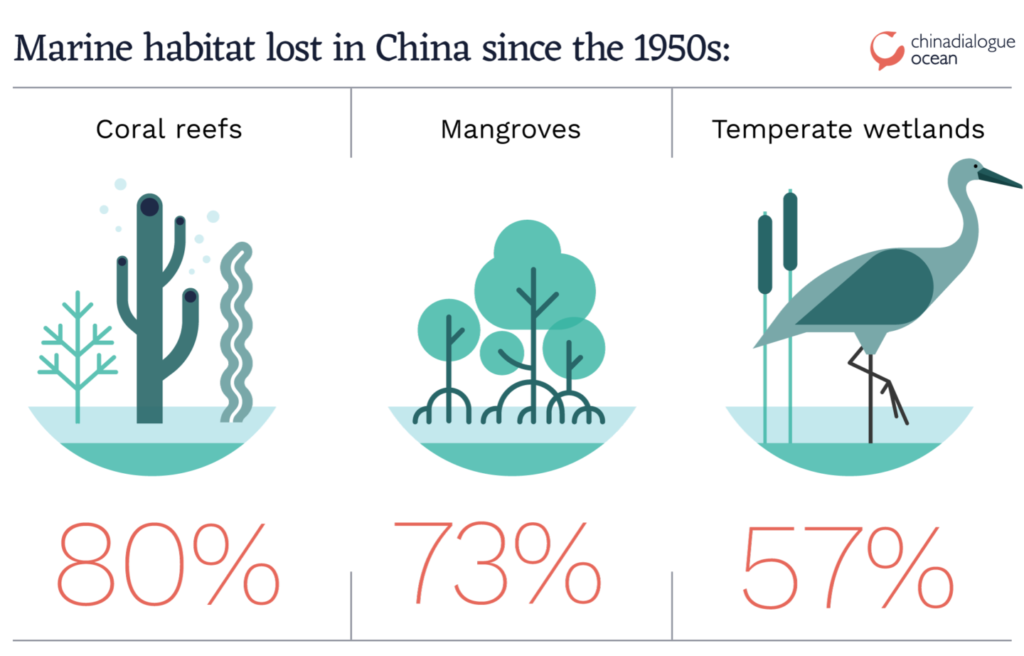

Often they too have serious environmental impacts. Open-water fish pens may not physically displace mangroves, but they can damage sea grasses and coral reefs by polluting the ocean with fish excreta, undigested feed and antibiotics. The penned fish can also damage wild fish populations if they escape and compete for food or damage the genetic integrity of their wild hosts by interbreeding.

So what now? Marine aquaculture is not going away. The world has to be fed. Aquaculture is the world’s fastest-growing source of food, and will soon exceed wild fish catches. Output is likely to double by 2050. Most of that growth is likely to be in Asia, which already conducts 90% of global aquaculture, and especially China, which is alone responsible for 60% of production.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE HERE >